Yikes.

/I’m more than a little concerned that I’m starting to develop tan lines from my mask.

That’s it. Just thought you needed to know.

I’m more than a little concerned that I’m starting to develop tan lines from my mask.

That’s it. Just thought you needed to know.

Not ten minutes ago, I left the store and started walking to my car.

Ahead of me, I saw a couple kids — probably late teens, maybe early twenties — bent over the sidewalk. Peering intensely at the ground. One of them was poking something with his foot. The girl with him, kept asking him questions, and cooing like she was trying to comfort something in pain.

I glanced over as I passed them by. On the ground between them writhed a dying honeybee.

“Can you flip him over?” the girl asked.

“I don’t want to get stung,” said the guy.

I leaned in to get a closer look. The bee wasn’t a him. It was a worker — one of the infertile females who do all the work in a hive. She was very pointedly writhing on her back, and her proboscis — her tongue — kept darting out of her mouth and back in.

I smiled at the couple, as I was a weirdo invading their space. “I think she’s done,” I told them. “When their proboscis sticks out like that, they’ve had a run-in with some pesticide.” They both looked at me with some mix of confusion, interest, and Who The Hell Are You-ism.

“I’m a beekeeper,” I explained. “She’s might even be one of mine. I only live a couple miles from here.”

“Miles?” the girl asked.

“Yeah, they’ll forage for up to five miles out of their hive.” I picked the bee up. She kept thrashing, tongue darting in and out.

“Does she still have her stinger?” The guy asked.

“Yep,” I said. “But she’s in no condition to use it.” I held her out so they could see.

We looked at the bee for a few seconds, the three of us. We didn’t say much. Only stood there in the late afternoon sun as the worker’s twitching slowed. “It was nice of you guys to stop,” I offer.

“It’s so sad,” the girl said.

“Yeah. But hopefully she has fifty thousand sisters back at home keeping the hive going.” Sad, yes. But a minuscule thing in the life of a hive. The queen lays up to two thousand eggs a day. One bee, a foraging worker, dying near the end of its useful life, is sad but no tragedy.

I laid the worker back on the ground. “Thanks again for stopping. Have a good weekend.”

I turned and walked to my car. I loaded my parcels, and heard a voice behind me. “Excuse me…”

The two had pulled up behind me in their car. The guy leaned out the window. “Is it true that bees are going extinct?”

That question. It’s a little complicated, and not especially conducive to a conversation out a car window in a mall parking lot. “Well…” I began. “Kinda. Wild pollinators are in trouble, sure. But if you’re talking about honeybees, we lose almost fifty percent year over year. And then we fight to bring their numbers back up. And we lose them again. It’s hard.” Shit, jared. Dire. “So don’t spray pesticides on your flowers.” That’s better. Less grim. An opportunity for hope.

The guy smiles, nods a little. Waves as he drives away.

It was just a little thing. A tiny bee. A small moment with two strangers. But it was a moment where two people took genuine interest and concern for a creature — a bug, and a stinging one at that — that they took time out their day to help it. And then bear witness as it slipped away. And listen to a scruffy stranger tell them how to make the world better for that bee. And the next one. And the millions after that. And ultimately for themselves and all of us.

It was a little things. But it was bigger than I expected when I shambled out of a mall on a Friday afternoon.

Today was a good day.

Have I mentioned that I’m keeping bees?

I am.

For the most part they’re fascinating, industrious creatures.

This afternoon, however, while working in my hives, I diagnosed one colony with a rare and unexpected condition.

These bees, it seems, are assholes.

In completely unrelated news: Costco sells Benadryl in bulk.

Now you know.

More to come…

One week ago, I had never been stung square on the nose by a bee.

Today, I can no longer say that.

Yep.

(More to come.)

This is definitely the muddiest my new shoes have ever been.

They’re laying on the floor, flopped haphazardly in front of the door as I am wont to do when I’m tired. And make no mistake—I am tired.

I’m not long back from a foray into the wilds of furthest Montana. My son and I visited the American Prairie Reserve – a huge, several-hundred-thousand-acre expanse of wide-open space destined to grow yet larger, as a refuge for American bison and all the animals that live in their biological shadow: elk, coyote, pronghorns, prairie dogs, black-footed ferrets – someday even wolves and bears.

It’s a wild place, and growing wilder.

I can see hundreds of miles from here.

The Reserve is a wildlife refuge, but it isn’t a National Park—not quite. It’s a public-private conservation partnership; a mix of state-owned land and land owned by the non-profit Reserve, along with participation by ranchers whose properties abut the Reserve itself. Ranchers who raise cattle.

Did I mention this is a wildlife refuge that also produces a line of grass-fed beef? It is.

Wild Sky Beef works with ranchers in Montana to produce grass-fed beef, primarily on prairie that has never been plowed. But what makes Wild Sky unique is that the Reserve pays ranchers a premium to create a more wildlife-friendly prairie – by installing wildlife-friendly fences, raising their animals in a predator-friendly manner, collecting animal population information via camera traps on ranch property, and more.

As more ranchers sign on, more and more prairie acreage becomes more and more hospitable to native fauna. Animals who once faced myriad dangers should they stray outside the boundaries of Yellowstone or Glacier National Parks find themselves with a more welcoming environment in the ‘wilds’ of human civilization.

And as Wild Sky works with more ranches in geographically important patches of prairie – say, between the aforementioned National Parks and the American Prairie Reserve itself – they begin to assemble something like a wildlife-friendly corridor between the enormous Parks system and the also-enormous Reserve.

Well, maybe not quite a corridor. More like wildlife-friendly islands. Like Frogger, really.

It’s giant, wildlife-friendly game of Frogger, using elk and bison and bears instead of 8-bit frogs.

Elk through a telescope. Also a good band name.

After paying a premium to participating ranchers for their wildlife-friendly efforts, the profits from the sale of Wild Sky Beef are put back into conservation efforts on the Reserve.

In time, the Reserve is slated to cover 3 million acres -- the largest wild space in the lower 48 states, and four times the size of Yosemite National Park. And, according to the plan, it will be a self-sustaining ecosystem. An American Serengeti.

I’m a big fan of the conservation role of large ungulates on grasslands. And I find these bison and cattle roaming across hundreds of thousands of acres in eastern Montana very exciting. As keystone species in a prairie ecosystem, as the bison go, so go the prairie.

But I'm equally excited to see optimistic people tackling enormous tasks that they're passionate about. To see people actively and forthrightly trying to make the world a better place -- in this case using enormous once-common animals to change the prairie into a better version of itself. Enlisting the hooves and habits of wild things to build the soil upon which a world rests; to make something grand and untamed and magnificent.

They call this Big Sky country, and not without reason. But there are big hopes and dreams here, too.

Some day, when the bison herd has grown yet larger and the bears are back and packs of wolves again harry the elk along the banks of the Missouri, maybe I'll return here.

Maybe I'll note how the wilderness has proliferated, and the human footprint diminished. Maybe I'll bring my son again, and he can look for his ancient footprints in the clay-thick mud.

But first, I really have to clean my shoes.

My almost-entire weekend, in a series of almost-tweets. Or maybe almost-haiku.

That I was almost too tired to write.

Asleep.

Why do I smell urine?

Awake.

Maybe it was just a dream.

Nope. Still there.

Dog looks guilty.

Dammit, Basil.

Up unexpectedly early.

Hose off dog. Hose off me. Hose off everything.

Pack car for long-promised camping trip.

A rodent of some variety has eaten a hole in my car's passenger seat. Awesome.

Discard foamy seatguts and throw a blanket on the seat.

Arrive at base of mountains. Smoke fills the air. #sandfire.

My car full of newbie campers.

Stop at fire station. "Will be be okay?"

Yeah. You should be fine.

Should.

Car tire low. Good thing I have a bike pump.

Drive into mountains. Wary family.

Reassurance.

Still wary.

Finally on trail.

Quarter-mile out, sole falls halfway off one boot.

Duct tape.

Child fills pockets with rocks.

Dude, those are heavy.

I love rocks!

Dude loves rocks.

Duct tape only sorta works.

Step, wobblewobble. Step, wobblewobble.

Mile after mile after mile.

Dad, can you carry my stuff?

Nope.

I'm tired!

You're tired because you've filled your hat with rocks, and hung it around your neck.

But I like rocks!

Leave them. We'll pick them up on the way back.

Arrive at camp.

Wanna summit nearby mountain. Boots don't.

Play in nearby forest instead.

Mountain springwater is delicious.

Duct tape fails completely.

Use the rest of my stash to re-repair boot.

Tent zipper fails. No vestibule for you.

Campfire. Lovely.

Sleep. Wake.

Coffee. Also lovely.

Lots of bugs.

Hike out of mountains.

Boot fails completely. No more duct tape.

Step, flopscrape. Step, flopscrape.

Dad, I'm tired.

Why are you tired?

My brother filled my backpack with rocks.

Drop the rocks.

Many miles.

Go full Colonel Kurtz.

Tear sole off compromised boot.

STEP, step. STEP, step. STEP, step.

Bugs are delicious.

Dreaming of better breakfast at quaint little mountain store.

Arrive at car.

Tire flat. Bike pump.

Car tires are big.

Drive to quaint little mountain store.

Quaint little mountain store is site of quaint little gigantic biker festival and juggalo gathering.

Too tired for juggalos. Drive on.

Kids fall asleep.

Drive to neighborhood restaurant smelling of nature and funk. Bugs in teeth.

Standing on flat ground, I lean. Boots uneven.

Get menu. Order one everything.

FEAST SUCH THAT WE SHAME OUR ANCESTORS IN VALHALLA.

Home.

Dive into beanbag like Scrooge McDuck into a pile of doubloons.

Nap. But not for long.

We're going to the opera tonight.

Seriously.

Shower.

Store. Picnic supplies for the Hollywood Bowl.

Tosca. Murder, sex, death.

(Amazing.)

Home again. Beat up from the feet up.

Words. Words, words, words.

Fin.

NOT PICTURED: JUGGALOS

Yes, cheesy title is cheesy. That's okay.

Happy holidays! Whatever you're celebrating and whatever you're doing, I hope you experience the best iteration of it yet.

Around this time of year, many people find themselves purchasing gifts. Know what makes a wonderful gift? Books.

With that in mind, here's a list of books I've either read, sampled, bought, juggled, stumbled across, or otherwise discovered in the past year. I hope they make your season a little brighter.

Defending Beef -- Nicolette Hahn Niman's tour-de-force analysis of how beef production -- done properly -- can be enormously beneficial to the environment. A somewhat counter-intuitive notion to some, but cattle can contribute mightily to the health of grasslands, many of which have suffered tremendously due to the eradication of the large ungulates who used to live there. If all you know of beef is factory farming, you need this.

The Homegrown Paleo Cookbook -- This one's a beast. Diana Rodgers provides over a hundred recipes, plus great info on everything from raising livestock to maintaining a garden to making candles and playing chicken shit bingo. (Note: do not make candles while playing chicken shit bingo. Do not ask me how I know this.)

The Paleo Solution -- Seriously? You've never read it? You're the one, eh? It could be called "How to Feel Better, Look Better, and Live Longer." It didn't come out this year, but do yourself a favor. Equal parts entertaining and enlightening.

Fed, White and Blue -- I met Simon Majumdar when we were on a panel together at the LA Festival of Books. He read from this book at the start of the discussion, and I was hooked. An endearing look at America through the eyes (and stomach) of an immigrant.

Gaining Ground -- At the same panel, I met Forrest Pritchard, a farmer and grass-fed cattle rancher who walks the walk. He's a hell of a guy, and a hell of a writer. Pick this one up. Part memoir, part inspiration, part instruction -- all great.

The Nourished Kitchen -- How to cook real food. A gorgeous book with great recipes. A charming and insightful book you should keep handy when you're in the kitchen.

Seriously Wicked -- I do, in fact, read about more than food and environment. You know Tina Connolly, right? Nebula-nominated fantasy writer (of The Ironskin Trilogy), making her first foray into Young Adult lit? This story about a teen girl whose adopted mother is a seriously wicked witch -- it's fantastic. Get it for the young adult or young at heart in your life.

The Serpent King -- Isn't even out yet, but it's available on pre-order. Another Young Adult piece, and a stellar coming-of-age debut by Jeff Zentner, and marinated in southern atmosphere. I'm eagerly anticipating this one. Get your order in now.

The problem with lists like these is knowing where to stop. So many books mean so much to me, that I could go on like this forever. So if you'd like another recommendation, let me know and I'll see what I can come up with.

Conversely, if there's something you think I haven't read -- and I really, really should -- let me know.

And have a happy, healthy holiday season.

jared

In the heyday of my misspent youth, I worked as a film grip in various low-budget and no-budget indie films across the Midwest.

The guys on my crew and I worked long hours, in oft-insane conditions, honing our cinematic skills so that some day in the hopefully not-so-distant future we'd be able to translate those hours into actual, real-life, paying gigs.

Our crew consisted of my Key Grip, his Best Boy, a couple of regulars like me, and a gaffer. Gaffers are the guys who work with the Director of Photography to execute his vision of how the scene should be lit -- the DP says "I want streaky shafts of low-angle sunset through Venetian blinds," and the gaffer makes it reality.

The gaffer on our crew was a guy named Ian. He was eleventy feet tall, with ginger hair to his waist. One afternoon, we were sitting in his apartment, which was furnished entirely with lawn furniture. ("It's cheap, durable, and comfy." Classic film crew thought process.) And we were talking about food.

In those days, we generally didn't eat well. We'd eat on-set at the craft services table, or at crew meals whenever we were lucky enough to get them. Otherwise, we ate like college kids do -- as cheaply and easily as possible.

"Except Potatoes," Ian said. "They're my thing. I don't mess around. I do good mashed potatoes." When I admitted that I didn't really have a go-to recipe for mashed potatoes, he looked at me as if snakes had just crawled out of my mouth. Wordlessly, he stood, scribbled something on the back of a hardware store receipt, and handed it to me.

I've kept that recipe as the basis for my mashed potatoes ever since. I've modified it some over the years, but the initial plan was solid. I wrote about these potatoes in my book, Year of the Cow, and I've had several requests that I share the recipe. With Thanksgiving fast approaching, I thought this would be a good time.

I don't make mashed potatoes often (glycemic index, yada yada). So when I do, I want to make them count. This is the recipe for my go-to mashed potatoes.

Go-To Mashed Potatoes

5 lb. Russet potatoes

8 oz. cream cheese

1 cup sour cream

2 teaspoons-ish onion powder

1 teaspoon salt (and to taste)

some garlic powder (to taste)

1/4 teaspoon white pepper

2 Tablespoons butter

Peel potatoes, cut into 2-inch chunks, and boil until soft.

Drain, add all ingredients, and mash to desired consistency.

Transfer to a well-buttered pan (9x9 baking dish/casserole works well).**

Using a fork, make small peaks in the potatoes, to provide a little more surface area for browning. The Maillard reaction is delicious. We are not heathens.

Bake in a 350 degree oven for 30 minutes, or until the peaks are slightly browned.

**Steps up to this point may be done up to a day in advance.

All my best to your and yours for a delicious holiday.

j

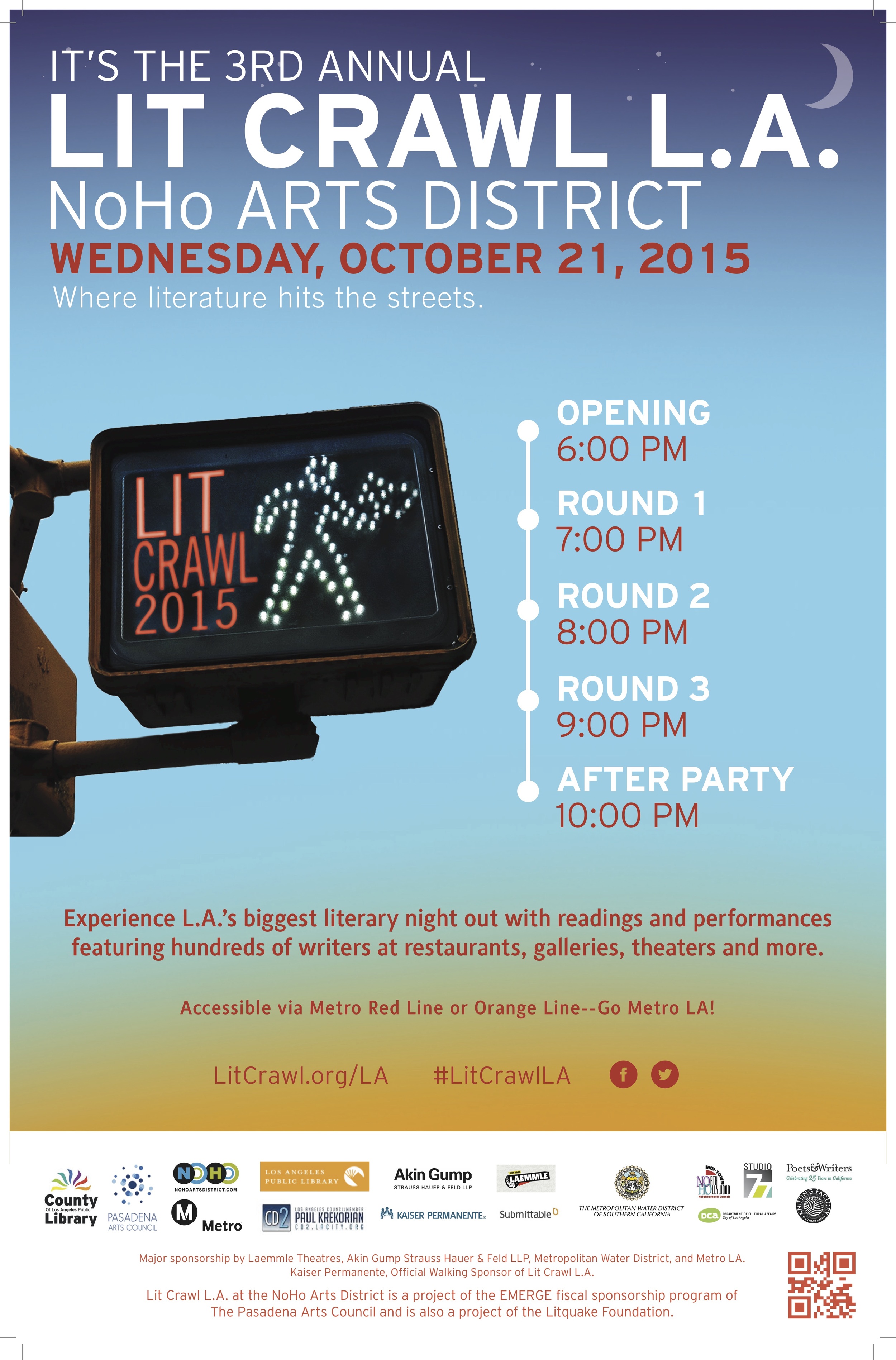

Wednesday! I'm going to be reading at the Lit Crawl Los Angeles.

I'll be presenting during Round 2 at Vicious Dogs. The event should be a lovely evening of arts and letters, and a celebration of the Los Angeles literary scene.

Swing by and say hello!

Recently, I've had the great privilege to talk with some wonderful people about some wonderful things. Most of those things involved food, health, sustainable agriculture, the meaning of life, and in one case, Romero movies.

For your ease-of-Googling, I've gathered my recent media appearances right here. In case you have a long car ride or something.

More in the pipeline, to be added as they're published.

At The Dinner Table, with Chef Bert Dumas:

We Choose Respect podcast:

An article I wrote for The Good Men Project -- "A Dad Discovers the Secret to Pleasing the Picky Eaters -- and Getting Them to Eat!"

And, finally, here's a link to my Op-Ed that ran in the LA Times -- "If we're going to eat cattle, let them eat grass."

More to come...

jared

I'm back!

Yes, perhaps you weren't aware I was gone. But I was. And now I'm not. There you go.

Traveled up California's central coast for a bit with the family to clear my head so I could re-fog it in new and interesting ways.

It was a lovely trip, and much fun was had by all. Here's what I learned along the way:

Redwoods are big.

Campfire coffee is definitively better than any other type of coffee, quality of beans notwithstanding.

When you wash your hair and smell campfire smoke, you know you were dirty.

Morro Rock is further away than it looks.

There is only One True Chowder, and it is New England Clam.

The sound a kid makes when he breaks his arm is entirely different than the sound he makes when he hurts himself to a lesser degree and is just mad about it and dramatic by nature.

Legos are dangerous. See previous entry. (Yes, seriously.)

California's central coast is home to many friendly and efficient hospitals.

Sometimes, sitting around with a kid and doing nothing is about the most fun a person can have.

A knife roll is the best investment a traveling food dork can make.

Running on a beach is simultaneously the best and worst way to do it.

I still don't understand the appeal of saltwater taffy.

--

It's good to be back, interwebs. Let's do this thing.

See you in the kitchen...

jared

'Tis the season -- for steaks.

And if you're like a lot of people, odds are good that steaks are going to feature into your weekend plans sometime very soon (*cough* *cough* Father's Day *cough*).

Most of those steaks will likely go down onto a very hot grill, seared for something in the neighborhood of ninety seconds per side, twice per side, with a rotation of about thirty degrees each flip to get those sexy grill crosshatches. Basically, as outlined here.

And that's cool. That's nice.

But sometimes, you want to pull together a steak that's a little more refined. Something, maybe, cooked indoors with a degree of sophistication. Maybe with a nice zin instead of a backyard beer.

I got you.

You should reverse sear those steaks.

Note the cooling rack under the ribeye. more on that later.

In the normal cooking process outlined above, you're applying a high degree of heat to the outside of the steak, which makes the meat beautiful and browned, due to the caramelization that occurs during the Maillard reaction.

As this heat passes into the meat, it cooks the center of the meat through. So if you're looking for something like a medium-rare center, you'll find very thin layers of medium, and even medium well as you near the surface of the meat. If you use high enough heat, those layers are thin, resulting in a maximum volume of meat at the desired medium rare doneness.

A reverse sear changes all that.

In a reverse sear, you cook the meat at low temp in an oven, until the entire steak is at the desired medium-rare doneness. Then you pull the steak from the heat and rest it, before finally dropping it onto a molten-hot hunk of slag iron to sear only the very surface of the meat to golden brown deliciousness.

That's a sexy steak. Here's how you do it.

Start with a steak at least one and a half inches thick. Something off the short loin would be nice -- rib eyes, strips, and the like.

**Placing the steak on a cooling rack is important. On a rack, warm air can circulate under the meat. This results in the meat cooking via convective (warm air moving around) and radiative (heat directly radiating into the meat) heat. These types of heat brown the meat more slowly. Conductive heat (touching the meat to something hot, like metal) brown things much faster. In this case, slow is what we're after. Put some aluminum foil underneath if you like, to make cleanup easier.

One of the many great things about this method is that since the meat has already rested before the sear, the juices agitated by the baking process have already redistributed back into the meat. Thus, the steaks are ready to serve immediately after the searing is complete.

Further, the searing process itself happens much more quickly. This is because a) the surface is already dry from the cooking process, so the sear isn't slowed by escaping moisture, and b) the surface temp is already elevated from baking, so there's less thermal distance to go before the Maillard reaction occurs.

At the table, you should discover a beautiful piece of nicely seared meat, medium rare from edge to edge.

If you haven't already decided what to do for Dad, this isn't a bad choice. (Though briskets are nice, too.)

See you in the kitchen...

jared

So, this happened.

I was back in LA, having just returned from my book tour in the Pacific Northwest. I'd made some vague motions toward unpacking -- though hadn't actually unpacked anything -- and otherwise had a day that was mercifully unscheduled.

And we had nothing to eat in the house.

This is important. Most notably because my wife will be out of town later in the week, leaving me alone with the kids. The adorable, running, screaming, climbing, maybe-setting-things-on-fire, chaos-on-feet kids.

That's cool -- I love spending time with the munchkins. And I love cooking with them. However in the event of a lack of time or an urgent need immediate protein, I can see the utility in cooking something big. Both to eat today, while I actually do have time to cook, and then to eat throughout the week, to be reheated at a moment's notice.

What do I know that's big? Brisket. Specifically, a whole packer brisket, cooked low and slow over hickory for a very long time. As this is a 12-pound cut of meat, this translates to a full day of cooking.

A whole packer brisket is, by some estimates, the apex of the barbecuing arts. Because of its tremendous size and irregular shape, it's a testament to the skill of the pitmaster.

Still tired from my trip, but intrigued by the challenge -- I decided that this needed to happen. Immediately.

And frankly, it turned out really well. So I wanted to share what happened, how I did it, and how you could do it, too. This is a great project to tackle for a weekend with friends, a week where you'll need some future easy meals on-hand, or for a special occasion. Say, for example, Father's Day.

Just saying.

Brisket is made up of the pectoral muscles of the steer. There's one brisket per side, and two muscles included in the cut, commonly called the flat and the point.

The flat is a big, well, flat plane of beef, too long to actually fit in my (admittedly undersized) kettle grill. The point isn't so much a point, as it is a large lump of meat that sits on top of the flat.

To visualize: if the flat is the American Midwest, the point is the Rocky Mountains. Kinda.

To cook this, I'll need to do some not-insignificant prep. The night before I'm planning to cook, I pull the gigantic cut, and do some trimming. One side of the brisket has a layer of fat up to about three-quarters of an inch thick. I trim that down to something in the neighborhood of a quarter-inch. Enough fat to keep the meat from drying out, but not enough that anyone's going to have to cut away a finger-thick layer of fat at the table.

I also separate the flat from the point.

That done, I hit the entire surface of the meat with more-than-generous amounts of kosher salt, and stashed it in the fridge.

The next morning, I got up early. And by early, I mean What have I done? early. Like 5 a.m. early.

I lope into the kitchen and start the kettle for coffee. Then, I pull the brisket from the fridge, and liberally apply a rub made up of black pepper, a (very) little granulated sugar, garlic powder and chili powder.

Flat on the left, point on the right.

I also injected it with copious amounts of beef stock. This cut is going to be on the heat for the better part of a day -- how long? who knows -- and the stock injections will keep it from drying out.

I fill a disposable roasting pan with water and place it under the grates of my gas grill so that it covers two of the three cooking zones. Over the third, uncovered, zone, I place three almost-fist-sized lumps of hickory. Ready to cook.

Finally, I fire up the burner below the wood, and prop a probe thermometer on a spare hunk of hickory (to measure the ambient air temp above the grates; lid thermometers are liars). When we're at 225, or close enough for jazz, the meat goes on. I jab another probe thermometer into the thickest part of the meat, and take a seat under a tree.

That's it. That's most of my cooking, done for the day. And it's all of 5:45 in the morning.

This is an excellent time to discuss the works of Iain M. Banks. Have you read him? He's a Scottish author who wrote literary fiction under the name Iain Banks, and then wrote science fiction material under the never-woulda-guessed-it pseudonym of Iain M. Banks. And when I say "science fiction," I mean grand, sweeping, make-Buck-Rogers-weep-in-his-Marsgarita space operas of epic depth and scale.

I'm reading my way (non-chronologically) through the works of Iain M. Banks -- the Culture novels in particular. At this particular juncture in the beef-cooking process, I crack open Consider Phlebas.

Several hours later, the meat temp is at 154. Quite a ways from my target doneness temp of 205, but we have arrived at the point in the cooking process known as The Stall.

Have you ever noticed that when you, personally, step outside on a hot day -- you sweat? This is because humans have evolved to utilize evaporative cooling. To wit: you sweat, this sweat evaporates off your skin, taking some of your body heat with it, leaving you cooler.

During The Stall, moisture has reached the surface of the brisket and is now evaporating off -- just like you on a July day in the Valley. This keeps the temperature of the brisket from rising. And since briskets are big, they have a lot of moisture. This could go on for a while.

The solution? A maneuver called the Texas Crutch. I momentarily pull the brisket, wrap it tightly in foil, and add a little beef broth to the package before placing it back on the grill.

The Texas Crutch does two things. First, the tight foil wrapping stops the evaporative cooling effect that was keeping the meat temp from rising. All that moisture is now staying right where I want it: in the meat. Second, the addition of the beef broth braises the meat slightly, helping to break down the connective tissues that can potentially make brisket tough.

Put differently, the Texas Crutch can cut your cooking time almost in half on a whole brisket.

Adequately Crutched, I close the lid and return to the exploits of Bora Horza Gobuchul and Juboal-Rabaroansa Perosteck Alseyn Balveda dam T'seif. (Yeah. It's that kind of book.)

Hey, I have a hammock I haven't used in a while. Let's see if it still works.

(It does.)

Finally, slowly, inevitably, the sun arcs across the sky and into the ocean. Night falls.

The meat temperature is finally up to 203. Close enough for jazz.

I pull the meat from the heat and stash it in a cooler lined with old beach towels. As per a recent NPR story (but known to pitmasters since long before that), the meat needs to rest.

Much like when a steak needs a ten minute rest after coming off the grill, smoked brisket benefits from a rest as well, and for largely the same reason: it allows the liquids in the cut, agitated from the cooking process, to redistribute themselves back into the meat as the meat cools. Unlike a steak, however, because a brisket is such a big piece of meat, it can rest for hours without any loss of quality. In fact, this rest improves the finished product rather dramatically.

Because the sun has set and people are hungry, I rest the meat for a mere hour and a half before placing it on a cutting board, unwrapping it, and examining the final result.

Beautiful.

A black crusty bark (it could be a little firmer, had I either a) not Crutched it, or b) put it back on the grill, uncovered for a few minutes to firm it up) and a loose, downright wobbly texture.

I slice into it. Not as much of a smoke ring around the edge as I would have hoped (more wood next time), but the texture and flavor are both lovely. With some roast asparagus I made during the resting period -- dinner is served.

So this, by any measure, is an honest day's work. Or, I should say, "work," as it was really a pleasant endeavor. A day with a book and a slowly smoking hunk of beef. A meal honestly earned and carefully crafted. I dig it.

Hint: if you have a father, this would be a lovely thing to make him for Father's Day. If you are a father, this would be a lovely thing to make on Father's Day.

It isn't hard. It can be persnickety. But it's a challenge well worth taking on.

Let me know how it turns out.

It's late in the Stone house. Everyone is asleep.

Well, everyone except me. I've always been nocturnal, to the betterment of some habits and the detriment of others.

We're just back from my book tour in the Pacific Northwest. It was an amazing -- if brief -- trip, and one I'm sure we'll be discussing for a long time.

I got to see some dear old friends, make some fantastic new ones, and spend hours in big, beautiful bookstores talking with people who share a love of the written word.

Highlights and notable moments:

Got to visit a museum dedicated solely to my son's favorite visual artist.

Had to temper my son's enormous physical enthusiasm by noting that his favorite visual artist works entirely in glass, and maybe he shouldn't wave his arms so much.

My first reading in a city that was not my own.

My SoCal kids got to play in rain.

My wife discovered a leather harness for carrying a six-pack of beer on a bicycle, and seriously considered buying it.

My second reading in a town that was not my own.

I signed some books.

My son signed his first book (mine).

My daughter signed her first book (not mine).

My son signed his second, third and fourth books (also not mine).

My wife stopped my four-year-old daughter from bum-rushing the podium during a dramatic moment in one of my readings. In doing so, got body-checked by our daughter and received a black eye for her troubles. (#motherhood)

Signed the special book at Powell's.

Too much amazing food to talk about.

Too many friends to count.

Too much happy to sleep.

Thanks to everyone I met, met up with, or almost met up with on the trip. Thanks to all the wonderful folks at University Book Store and Powell's for putting me up, and thanks for everyone who came out to talk about books and beef on a weekday.

See you at the next one.

Recently, I had the privilege of speaking with the inimitable Robb Wolf on his podcast the Paleo Solution.

It was a fantastic chat -- I think we covered every topic under the sun. Give it an hour, and we'll give you sixty minutes.

You can check out the podcast here.

Lesson learned.

Here's another excerpt from my post-reading Q&A in Los Angeles. (A quick primer on how NOT to cook a meal.)

In anticipation of my Seattle and Portland events, here's an excerpt from my post-reading Q&A in Los Angeles.

In it, I detail how I found my narrative in the process of cooking an entire cow.

I recently wrote an Op-Ed for the LA times on the subject of grass fed beef and the environment.

Available on the LA Times website, and reprinted here, below.

---

Stories about impending environmental apocalypse circulate almost daily, especially in drought-ravaged California. Many of these stories tend to blame agriculture — and specifically, beef — for gobbling up our resources. Though numbers vary widely and are hotly contested, some researchers estimate that it takes 1,800 gallons of water to produce each pound of beef.

The real problem, however, isn't cattle. It's industrial feedlots, where more than 70% of U.S. cattle eventually live.

In an industrial feedlot, potentially thousands of animals are packed together in an enclosure of bare, unproductive dirt. Nothing grows there. Operators have to bring in water for the cattle to drink, and for the enormous manure ponds that contain the cattle's waste. But the majority of the water used in raising industrial cattle goes into growing their feed. These operations are tremendously resource-intensive.

If you eat beef, grass-fed cattle are a better option. Those cattle are a healthy part of a larger ecosystem.

Raised wherever grass grows, these cattle don't need manure ponds. While they do need a source of drinking water, a rain-fed pond suffices in most cases. In turn, the animals' grazing improves the health of the grassland, often dramatically, and increases the ecosystem's water retention.

These cattle, moreover, can graze on marginal land that doesn't have any other agricultural worth.

Several years ago, I purchased an entire grass-fed steer to feed my family. It was raised in an olive orchard, eating what the ranch considered "waste product": the grass and scrub that grew between the olive trees.

Grass-fed cattle can graze on marginal land that doesn't have any other agricultural worth. -

Raising cattle for food isn't necessarily incompatible with environmentalist or humanitarian agendas. Because cattle can thrive on otherwise unproductive land, the charity Heifer International provides livestock as a sustainable gift to poor families, mostly in the Third World.

Further, recent research suggests that properly managed grass-fed cattle can help capture and store carbon in grassland soil. In addition to making the soil more nutrient rich and better able to hold water, one study found this process happening at a rate that could actually help offset the rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide. It also showed that properly managed cattle pastures had levels of soil organic matter comparable with those of native forests.

Of course, if there isn't enough rain for very much grass, there isn't enough rain for very many grass-fed cattle. That's where we are now in California.

In times like these, efficiency is paramount. And the most efficient way to use beef is to buy in bulk, up to and including an entire animal. The single steer I purchased lasted my family for nearly five years. I brought home every bit of the beast and used it all. I probably ate less beef per week than the typical consumer because I was trying to make the best use of every morsel.

According to the U. S. Department of Agriculture, Americans waste an estimated 30% of the food we produce. Reducing that percentage would greatly increase the efficient use of natural resources, including water.

Faced with the harsh long-term realities of climate change and the immediacy of the California drought, the choice is clear: If we're going to eat cattle, let them eat grass.

As a guy who bought a whole cow, I'm asked a lot how to cook this-or-that cut of beef.

Of course I'm happy to share whatever knowledge I've gained, but I also thought it would be useful to build something to get those just entering the kitchen started off on the right foot.

To that end, I've built a series of very brief top line summaries of all the beef primals. They should at least get you started if you have a question about a particular cut.

You can find them at the top of this page, under the menu "About Beef."

I've also built a very brief outline of cooking hot and fast -- for cuts without a lot of connective tissue -- and low and slow braises, for those cuts that have some connective tissue to break down.

Soon, I will be adding a section on barbecue, as well.

Finally, I've also included a section on how to actually go about buying a grass fed steer, should you be so inclined.

I hope you find them helpful.